“The Little Ones”

Matthew 18:1-5, 10-14

September 7, 2008

I spent a part of my vacation on an island in Maine, just a couple of days, in which I had an opportunity to be with some little children up close for the first time in a long time. Of course, as you know, there are little children here at St. Sociable, and I do have the great fun and privilege of getting to know them as they come and go, speaking with them during children’s messages (or any time, really), occasionally playing guitar to accompany their singing during Vacation Bible School or Rally Day. But it has been quite a few years since I spent time with little ones on a daily basis, playing with them, watching them go.

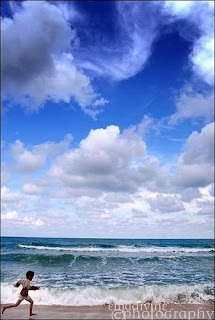

There were two little ones in the house where I was staying, M. and S. M. is five and S. is three. One day their dad G. and I went to the beach with M. and S. and teenagers Petra and E. Once there, my dim memories of my own children came flooding back. There is no containing children on a beach. It’s not a playpen or even a rec room. M. and S. began by running back and forth and in circles. Then they explored the rocky coastline, until their toes hit the water. Then, enthralled, they looked back at their dad for permission, and began a long ballet of going in and out of the water… going in up to their ankles… and then running out again… then going in up to their calves… and running out again… then going in up to their knees… and running out again… then to their thighs… and running out again… then to their waists… and running out again… and finally throwing themselves in and coming up sputtering, clapping, squealing with glee. I need to add at this point that, I consider myself a polar bear, and pride myself on swimming in any temperature the Atlantic Ocean can throw at me. I couldn’t get past my knees. It was freezing.

Being with M. and S. was a trip back in time, not just to memories of my own children, but also to my own memories, of times when I was willing to immerse myself in play without wondering how many calories I was burning or whether my stroke looked good, of times when the ocean was a brand new mystery, thrilling, exciting, something my parents had to drag me out of at the point my lips were blue and my fingers were prunes, of times when time stood still because I was lost in the wonder of it all. There is nothing like childhood, nothing in the world.

And so we have Jesus this morning, who is asked a question about greatness, about social rank, to borrow a term from the current presidential campaign, about who were the “elites.” If we were to look back at how the story of Jesus and his teaching has been unfolding throughout of Matthew’s gospel, we would notice that Jesus has already done quite a lot, trying to change the way his followers look at the world. He’s been turning things upside down. His sermon on the mount is about as topsy-turvy as things get: Jesus pronounces blessings on the poor (in spirit), the mourning, the meek, the persecuted… all those people whom society completely disregards: the least, the lost. Jesus says, no. These are the leading citizens in the kingdom of heaven (Matthew 5:1-12). Jesus has spent long hours, days and nights, weeks and months, healing people whom the rest of the world has abandoned, and feeding the hungry.(Matthew 8, 12, 14). Jesus has sent his disciples out, not as conquerors, but as humble teachers, taking almost nothing with them except the gospel—which, as it turns out, is everything they need (Matthew 10). Jesus has already told the disciples what has to sound like very bad news, that anyone who wants to follow him has to be ready to take up a cross, and be prepared to lose a life (Matthew 16). In every possible way Jesus has spent the first 17 chapters of this gospel explaining to his followers that things, according to the wisdom of God, are different than their expectations. God’s kingdom doesn’t look one iota like earthly power structures, and God doesn’t look one iota like earthly rulers.

And now the disciples want to know about greatness. Who is the greatest in the kingdom of heaven? Is it the most faithful disciple? Is it the one who wins the most converts, or the one who suffers the most? Is it the one with the best track record for healing, or who does the best job at feeding the crowds? Once again, Jesus turns things on their heads. Instead of producing the strongest or the smartest or the most spiritual or the most stunningly mature person, Jesus calls a child, and puts her right in their midst. Here is the greatest, he says. Be like this. Be like this child.

Our modern notions of children need to be put aside so that we can fully understand what Jesus is saying here. Our society pays wonderful lip service to the idea that our children are the most important things in the world, our precious priorities. Children and childhood have been sentimentalized, and elevated in the popular imagination as perfect and innocent. Judging by the advertising aimed at parents, it is clear that children’s wants and needs have become the basis of an economy, from toys and dolls to soda and snacks, to skateboards and bikes, to iPods and video games. We have a law called “No Child Left Behind,” whose purpose is to make sure our children are educated. But as you and I both know, our actual behavior and policies do not bear that lip service out. One in ten children in the US are uninsured, and have no adequate health care, and 17% of our children… almost one in five… live below the poverty line. Of the children who live in poverty, they are statistically far less likely to have a regular bedtime and a regular mealtime than children whose families are more economically sound.

For all these troubling statistics, children today are still better off than children in Jesus’ day. Infant mortality rates were astronomical, with close to one in three children dying before weaning age. Of course, that’s close to the current infant mortality rate of one child in five in Afghanistan, which is so radically different from the current US infant mortality rate of 8 children per 1000. Parents needed children to help with the production of food, with farming or fishing processing grain. Children were looked upon as part of the labor force, and families knew better than to get too attached to them until they were five or so. In a society that was stratified with tremendous wealth and power at the top and crushing poverty, illness and hopelessness at the bottom, nearly all children lived at that bottom.

But there is something that was as true of children 2000 years ago as it is today. Little ones do not come into the world with an innate desire for status and power. The idea of a two year old wondering how to achieve greatness is absurd. Children come into the world with one job and one job only: they are wonderfully made to absorb, to take in, to learn, to acquire understanding. This, of course, is why we have to watch them so closely… they live in a state of dangerous wonder. Everything they see and touch and experience is enthralling to them… think of M. and S. running in and out of the ocean. Everything about God’s world and the thrilling experience of discovering new sensations bowls them over, delights them, sends them through the moon.

How do we achieve greatness? Not the kind of greatness that gets you elected to office, or earns you millions of dollars, but the kind of greatness that finds you a place in God’s reign. We become like children… completely oblivious to position and rank, and completely open to a “volatile mix of astonishment and terror, awe and risk, amazement and fear, adventure and exhilaration, tears and laughter, passion and anticipation, daring and enchantment.”[1]

This is not something that comes naturally to most of us. Most of us, no matter what our life’s work, are caught up in a world that evaluates us, tells us brutally when we’re successful or failing. We feel we barely have time to go through the motions of faithfulness, and then Jesus suggests this overwhelming and somewhat puzzling project of remaking ourselves in the image of four-year-olds.

As with anything else, we start where we are. Today, why not start with communion. We start with a table that has been set for us, and bread that is so much more than bread, and the fruit of the vine that becomes for us so much more than grape juice. Why not try to come to this table with childlike hearts… hearts full of wonder and anticipation. Hearts stirred to excitement, because of Who it is we are likely to meet there. Hearts, perhaps, tinged with fear, because this might just change our lives. Let’s start where we are: coming to the table with a hymn of childhood on our lips and the dangerous wonder of childlike faith in our hearts. Thanks be to God. Amen.

[1] Michael Yaconelli, Dangerous Wonder: The Adventure of Childlike Faith (Colorado Springs, CO: NavPress, 1998), 29.

Image courtesy of Emadivine at Flickr.

1 comment:

thank you or this wonderful sermon.

Post a Comment